The Evolution of an African American Aesthetic: Innovation Rooted in Oppression (1865–1939)

- murant9

- May 26, 2025

- 5 min read

The period immediately following the abolition of slavery in the United States in 1865 marked the beginning of a new era for African Americans. Faced with entrenched racism, systemic oppression, and a lack of access to formal education or resources, African Americans navigated these challenges by engaging in a unique form of ingenuity. This ingenuity manifested itself not only in the social and economic realms but also in a burgeoning African American aesthetic—one forged in response to oppressive conditions and deeply intertwined with the lived experience of Black people in America. In particular, the contributions of African American inventors from 1865 to 1939 reveal a form of creative expression that was both utilitarian and deeply artistic. These pioneers innovated within the confines of their circumstances, often without access to the traditional mediums of art—painting, sculpting, or writing—yet produced creations that possessed a distinct artistic and cultural value.

In this exploration, we delve into the characteristics of this emergent aesthetic, the role of early inventors in shaping it, and how this form of creation not only fulfilled practical needs but also signified the birth of a uniquely African American art form.

The Emergence of African American Inventors as Cultural Pioneers

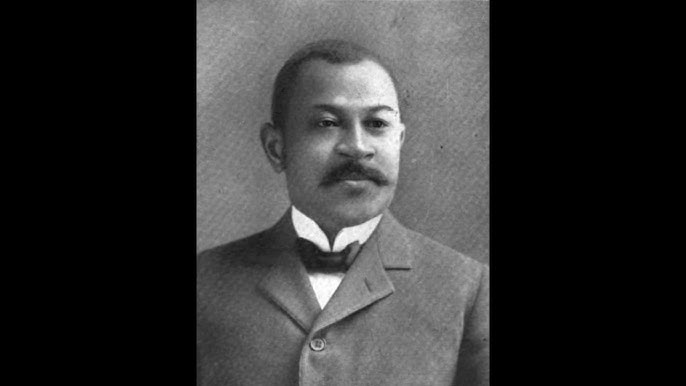

Between 1865 and 1939, African Americans faced systemic obstacles designed to limit their economic, social, and intellectual advancement. Denied equal access to education and barred from many industries, African Americans had to rely on creativity and resilience to carve out opportunities. Early African American inventors, such as Granville T. Woods, Elijah McCoy, and Lewis Latimer, exemplified this spirit of innovation. These men were not merely inventing devices; they were envisioning solutions to problems that stemmed directly from the experiences of a racially oppressed people.

Woods, for example, is credited with over 50 patents, many of which were related to the railroad and telecommunication industries. His innovations enabled more efficient and safer railway systems, but more importantly, they addressed a critical infrastructure need in a country where African Americans were often relegated to manual labor. Similarly, McCoy’s lubrication system for steam engines dramatically improved industrial machinery performance, and his work was so advanced that the term “the real McCoy” became synonymous with authentic, high-quality innovation. These inventors were not simply filling technological gaps—they were negotiating the oppressive circumstances they were forced to operate within. Their creations can thus be seen as early expressions of a uniquely African American aesthetic, an art form of utility born from necessity and shaped by the social realities of post-slavery America.

Defining the African American Aesthetic in the Context of Innovation

The notion of art often brings to mind visual and performance arts—painting, sculpting, literature, and music. However, the African American inventors of the late 19th and early 20th centuries created a form of art that transcended these traditional boundaries. Their art was not defined by beauty or form alone, but by the dual functions of utility and survival. It is this intersection—where art becomes both a means of aesthetic expression and a tool for enduring oppression—that distinguishes the African American aesthetic from others.

African Americans during this time were largely barred from participating in the formal art world, which was often an exclusive domain reserved for white artists. Despite this, they found ways to create. While they were not allowed to paint on canvas or sculpt in marble, African Americans used their circumstances as the canvas and their ingenuity as the medium. The products of their labor—patented inventions and mechanical innovations—carried the imprint of cultural survival. These were not simply tools or machines; they were the functional equivalent of paintings and sculptures that could transform the physical and social landscapes of African American life.

This aesthetic, rooted in necessity, reflected the conditions from which it emerged. It was unique in that it evolved in response to the dehumanizing effects of slavery and the Jim Crow era, but also because it encompassed the need for innovation that directly addressed the practical and emotional needs of African Americans. Where others might see only utilitarian objects, we see works of art that tell the story of resilience, survival, and cultural identity.

Art by Necessity: The Creative Process of Invention

In the absence of formal artistic outlets, African American inventors of the post-slavery era used their creativity to address the needs of their communities. This creative process, though often overlooked, bears striking similarities to the artistic process found in more traditional forms of art. Like painters or sculptors, inventors must conceptualize, experiment, and refine their ideas before arriving at a finished product. In the case of African American inventors, the finished product was often a solution to a problem posed by oppressive social conditions.

For example, George Washington Carver's work with agriculture can be seen as more than just scientific innovation—it was a kind of ecological art that addressed the destruction of the land and livelihoods of sharecroppers, many of whom were formerly enslaved individuals. His development of crop rotation and soil restoration techniques not only helped African American farmers survive economically but also reflected a deep connection to the land that had been violently denied to Black people during and after slavery.

Similarly, the inventions of Henry Blair, the second African American to be granted a U.S. patent, were developed with the goal of improving agricultural efficiency. His seed planter and cotton planter were not just mechanical tools; they were designed to make life easier for laborers who were often African American sharecroppers, burdened by the legacy of forced labor and poverty.

These innovations reflect the creativity of survival. African American inventors like Blair and Carver were engaged in an art-making process that was driven by necessity but infused with an underlying cultural and aesthetic significance. Their inventions functioned not only to make life easier but also to reclaim a sense of agency in a society designed to deny it.

The Legacy of African American Innovation and the Foundations of a New Aesthetic

The contributions of African American inventors from 1865 to 1939 laid the groundwork for what we might now recognize as a distinct African American aesthetic—an aesthetic that is not limited to traditional art forms but includes the creative act of invention itself. These pioneers, operating within a context of oppression, developed innovations that were both practical and profound. In doing so, they created something more than mechanical devices; they crafted objects that encapsulated the struggles, triumphs, and ingenuity of a people forging their own paths.

In retrospect, the inventions of African American pioneers during this period represent more than just technological progress. They reflect a form of cultural production that was as much about survival as it was about expression. In a society that sought to strip African Americans of their humanity, these inventors created works that asserted their intelligence, creativity, and dignity. This was art born out of necessity, and it laid the foundation for future generations of African American artists, thinkers, and creators.

As we examine this unique art form today, we see that it speaks not only to the past but also to the enduring spirit of innovation and resilience that defines the African American experience. This aesthetic is one of transformation—taking the raw materials of oppression and fashioning them into something new, something distinctly African American, and something that will continue to shape the cultural landscape for generations to come.

Comments