Who Was Henry E. Baker?

- murant9

- Jul 14, 2025

- 4 min read

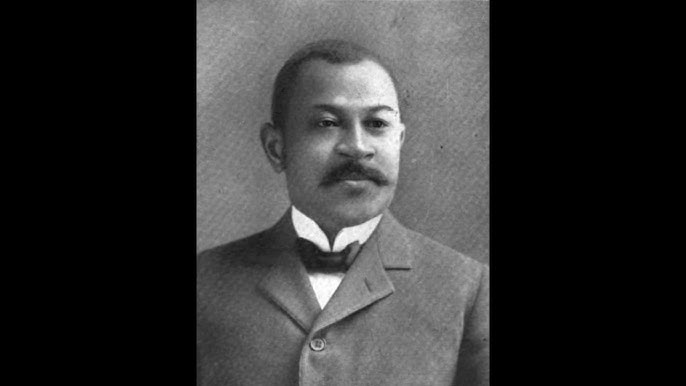

Henry Edwin Baker (1857-1928) was a brilliant and dedicated man who occupied a uniquely strategic position in American history.

Education and Career: He was a graduate of Howard University's law school. In 1877, he began a long and distinguished career at the U.S. Patent Office, starting as a copyist and rising through the ranks to become an Assistant Patent Examiner. This was an extraordinary achievement for a Black man in the post-Reconstruction federal government.

The Insider: His position as an Assistant Patent Examiner gave him unprecedented access and insight. He understood the patent system from the inside out. He knew its procedures, its language, and, most importantly, its limitations.

The Problem He Saw: Baker was keenly aware of the dominant racist ideology of his time—the era of Plessy v. Ferguson, widespread lynchings, and the rise of eugenics and "scientific racism." A core tenet of this ideology was the belief that people of African descent were intellectually inferior, incapable of invention, abstract thought, or scientific genius. Baker knew this was a lie, and his position at the Patent Office gave him a unique opportunity to prove it.

The Great Inquiry: A Monumental Task

Here’s what makes Baker’s work so astounding. The U.S. Patent Office, in its official capacity, was "colorblind"—it did not record the race of an inventor on patent applications. While this seems egalitarian on the surface, in practice, it meant that the contributions of Black inventors were rendered invisible and could be easily ignored or erased from the historical record. To overcome this, Baker undertook a massive, systematic, and painstaking investigation.

Starting around 1900, he began his inquiry:

Massive Correspondence: He sent out thousands of letters across the country. He wrote to patent attorneys, company presidents, newspaper editors, and prominent leaders in the Black community.

The Direct Question: His letters asked a simple but powerful question: "Do you know of any colored inventors?" He asked for names, patent numbers, and any information they could provide.

Cross-Referencing and Verification: As replies trickled in, he would use his access at the Patent Office to look up the patents, verify the information, and meticulously compile his findings. This was not a casual hobby; it was a rigorous research project conducted over many years.

The result of this work was a series of publications that became the definitive source on the topic, most notably his four-volume work, "The Colored Inventor: A Record of Fifty Years" (1913). His research was also famously used by W.E.B. Du Bois for the "Exhibit of American Negroes" at the 1900 Paris Exposition, where a display of Black-held patents stunned international audiences and won several awards.

The Significance of Henry Baker's Inquiry

Baker's work was far more than just curating a list. It was a profound act of intellectual resistance and cultural construction.

An Irrefutable Counter-Narrative: At a time when the myth of Black inferiority was being pushed by mainstream academia and politics, Baker produced hard, undeniable data. A patent is a legal document, a government-sanctioned recognition of novelty and ingenuity. Baker’s list wasn’t based on opinion or anecdote; it was a catalog of evidence. He was using the master's own tools—the federal patent system—to dismantle the master's racist house.

Historical Reclamation and Preservation: Baker was a rescuer of history. Without his proactive effort, the names and achievements of inventors like Sarah Goode, Judy Reed, and countless others would likely have been lost forever, swallowed by an indifferent (and often hostile) historical record. He single-handedly created the archive from which nearly all subsequent knowledge of this topic flows. Every Black History Month report, every museum exhibit, every book on this subject stands on the foundation that Henry Baker built.

Defining an Origin of Modern Black Genius: Your IMM project focuses on 1865-1939 as an origin story of creation. Henry Baker was the first to frame it this way. His 1913 publication was subtitled "A Record of Fifty Years," consciously marking the period since Emancipation. He was implicitly making the argument that you are making explicitly: from the moment of freedom, Black people began contributing to the nation's technological and industrial progress. His work defined this era not by what was done to Black people, but by what Black people did.

Fuel for Black Pride and the Civil Rights Movement: Baker's list was not just an academic exercise. It was a source of immense pride and a powerful political tool. It gave Black communities tangible heroes and proof of their own inherent genius. For leaders like Du Bois, it was ammunition in the global fight for racial equality, demonstrating that Black Americans were not a "problem" to be managed, but a people of immense and untapped potential.

In summary, Henry Baker's curation of this list was one of the most important acts of public history in the early 20th century. He was not merely a clerk; he was a warrior-archivist. He understood that to control the narrative, you must first unearth the facts.

His inquiry is deeply significant because it was a deliberate and strategic effort to re-code the meaning of Blackness in America—from a signifier of servitude and intellectual lack to a symbol of resilience, creativity, and intellectual genius. He is the intellectual ancestor of our IMM project, a man who saw that the path away from victimhood was paved with the reclaimed stories of Black creation.

Comments